I used to write books about druids. Then I wrote books about philosophers. Then I wrote a six-volume urban fantasy series. Now I’m writing a science fiction novel, and a second edition to a college textbook on logic. A friend remarked to me yesterday that it looks like I’m randomly re-inventing myself, and leaving people confused.

I disagree: I think I’ve been completely consistent to myself the entire time– but to explain why, I need to tell a story.

In 1982, I was in grade three, and my teacher put me on an enriched reading program, separate from the rest of the class. I read the autobiography of Michael Collins, the Apollo 11 astronaut. I think that around the same time, I saw Star Trek: The Motion Picture. And my dad bought a telescope, and showed me how to use it to project an image of the sun on to a screen, so we could count sunspots. Meanwhile, every year someone would give me for my birthday a bag of mixed Lego bricks, which almost always included some of those wonderful blue and grey spaceship themed pieces. Soon I was creating entire fleets of spaceships, some of them G-Force style fighters, and some of them Star Trek style exploration vehicles. My Lego astronauts had names like ‘the leader’ and ‘the one who likes fighting’ and ‘the curious one’. I had my own Trek style space-exploring federation. I built base stations that resembled temples– one of them was a tower, which I built almost two meters tall, and which was the home for the fleet’s leader. He had a black body and legs, and a blue captain’s hat, and a scratch over his mouth which erased part of that famous Lego smile. He also had mystical Jedi-like powers; and he sometimes secretly consulted a disembodied head for guidance. This being a child’s fantasy, after all. I never gave my space fleet a name– it was enough to know the fleet was my fleet. These were my first science fiction stories.

My childhood sci-fi fantasies tended to look rather surreal, like this frame from Star Trek The Motion Picture.

In the fourth grade, I committed one of those stories to pen and paper. It was about a group of rabbits who build a rocket ship, but on their first launch something goes wrong and they found their ship on course to crash into Jupiter. I never did finish writing the story, but I drew lots of doodles of the rocket ship and its crew all over my notebooks. Probably in the same year, I read Arthur C Clarke’s 2001, and Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles and The Halloween Tree, and Something Wicked This Way Comes. Thinking brave new thoughts about infinity and reality cannot help but do weird things to a young mind— in fact, at the time, some of my teachers led me to believe that such books were as dangerous as experimenting with drugs. Naturally, therefore, I read them anyway– often in my secret place in the forest outside my village; often under my blankets at night, with a pen-light given to me by my grandfather. In high school I kept the habit. My teachers asked me to read The Grapes of Wrath and The Stone Angel. Instead I read A Canticle for Leibowitz and Rendezvous With Rama. And I read Camus’ The Plague and Sartre’s No Exit, but that’s another story.

In my first month as a grad student at the University of Guelph, I met Prof. John Leslie, just after attending a lecture he delivered on the Carter-Leslie Doomseday Argument. Although I ended up writing my Masters thesis on a different topic, and my doctorate on another completely different topic, the logic of the argument always loomed in my mind. I bought Leslie’s book The End of the World right away, and it stayed on my bedside table for many years. Usually beside a copy of Watership Down.

Many more years after that, as a professor at Heritage College, I read Azimov’s Foundation trilogy. And around the same time, several NASA-funded scientists published an essay called “Human and Nature Dynamics (HANDY)“: a mathematical model they had invented, which shows how “over-exploitation of either Labor or Nature results in a societal collapse.” And then things began coming together. I thought of Michael Collins again, and the Doomsday Argument, and my story about the rabbits in their star-crossed rocket ship, and all the sci-fi that my teachers wouldn’t let me read in class but were secretly proud that I read anyway. Azimov’s story features a fictitious social science, Psychohistory, which predicts the mass movements of huge populations of people; the Carter-Leslie Doomsday Argument together with the HANDY model seemed like the obvious real world analogy. And I found I still wanted to understand it better, and write about it.

That’s where Lorelei Bloem, the heroine of my scifi novel, comes from. She is not a new self-reinvention. She lives in a world which has always been with me. She’s the scientist, philosopher, and ecologist, who discovers the evidence that the world has a bright and good future– but no one believes her. I have loved her for a long time. And I’m almost ready to share that love with everyone.

Nobody in life is entirely ‘one’, in the sense of being a unified person, having a single unchanging identity throughout her life. In my forty-two short years I have already lived many lives; I am as different to my ten-year-old self as I am different to my next-door neighbour; I have been a different person to different people and different communities. I might ask, as Walt Whitman asked: “Do I contradict myself?” And I can answer the same way: “Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” But there is a thread tying them all together, a long red string that was sewn together from other strings before I was born, and which I lay on the ground behind me as I walk, like an explorer in a labyrinth keeping his finger on the way back to the door. That red string is my story, my narrative, my logos; it is that which emerged whenever I found myself facing an immensity, and instead of running away from it, I sought to understand it.

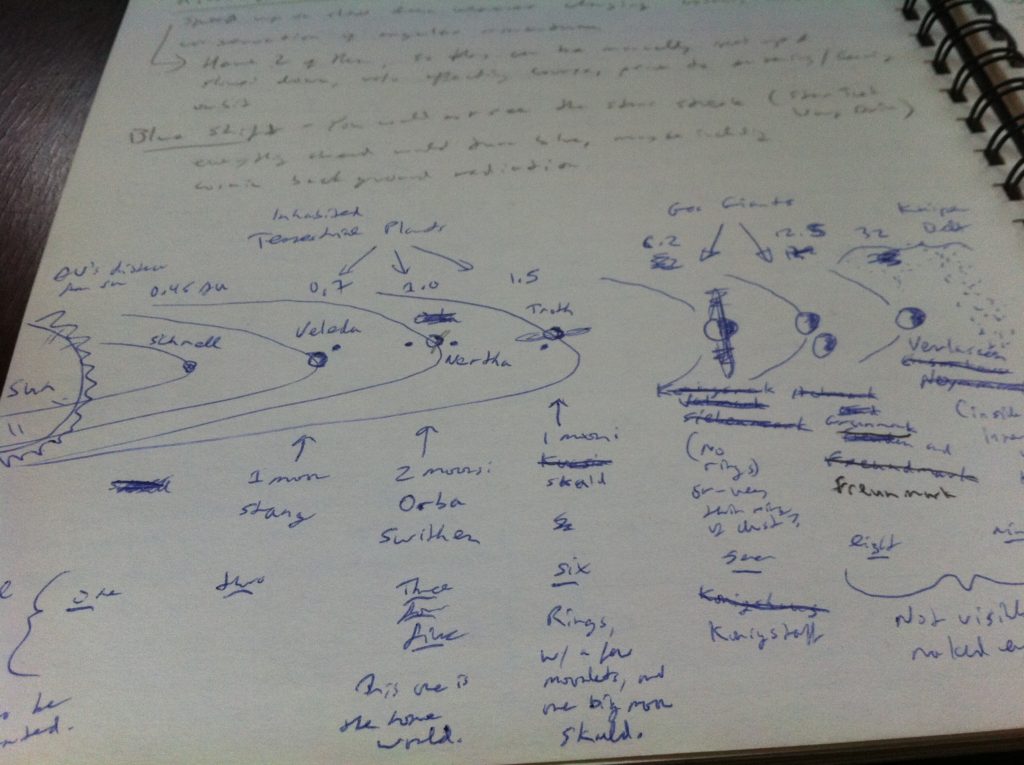

The names of the planets and moons in the fictitious solar system of my novel.

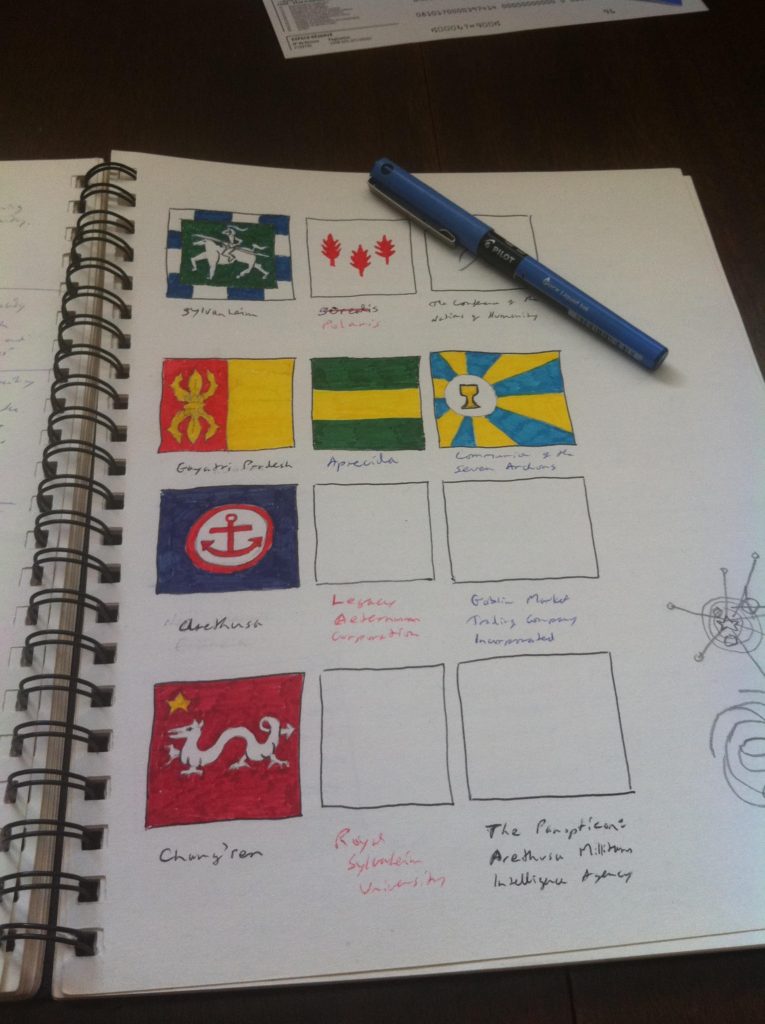

Flags and other symbols for the various political factions in the novel. Unfinished and very subject to change.

Postscript: Here’s the (draft) marketing text, for when I eventually seek an agent and publisher.

Tagline:

A scientist discovers a crashed alien space probe, thereby triggering a new space race, and a new cold war.

Â

Cover copy:

A bored technical team discovers a crashed alien space probe on Verlassen, the furthest dwarf planet from the sun. The discovery triggers a new space race, to build a starship and travel to the planet that the probe came from, only nine light-years away. Lorelei Bloem, the team’s science officer, persuades The Conference of the Nations of Humanity, a global diplomatic and humanitarian agency, to build a ship. But the competition includes military juntas, corporate oligarchies, and fanatical religious groups, all intent on sabotaging her work. She calculates that the ship must be built in less than sixteen years: after that, the looming cold war between the superpowers will collapse the world’s economy and biosphere. Under pressure from all sides, and thrust into the spotlight unprepared, her choices will determine the future of civilization.State of the Manuscript:

The first draft is 80,000 words and almost finished. I expect to have a complete first draft by mid May, 2017.

Post-postscript: My friend also asked me, Why is my lead character a woman? The short answer is, I have long been fascinated by the story of the Lorelei, the Germanic siren-spirit who lives in the rocks beside a sharp bend in the river Rhine. I have a lot of lingering nostalgia for my two visits to Germany, in the summer and autumn of 2004.

And because the gods of philosophy are women: Saint Sophia, and Urania, for instance.

Urania, Muse of mathematicians, astronomers, and philosophers.

Although my Lorelei isn’t Greek, and I haven’t yet asked her whether she wears a tichel.

Also, because of the magnificent song by The Pogues.

And because women can do things in stories that men can’t do; and women also face different (usually bigger) social obstacles. My acknowledgement of the literary politics of our time.

And because– well, it’s best I keep my last reason to myself. When you read the novel, I hope you’ll see.

Pingback: Two cover-copy possibilities for my scifi novel | The North West Passage

Pingback: My writing plans for Autumn 2017 | The North West Passage