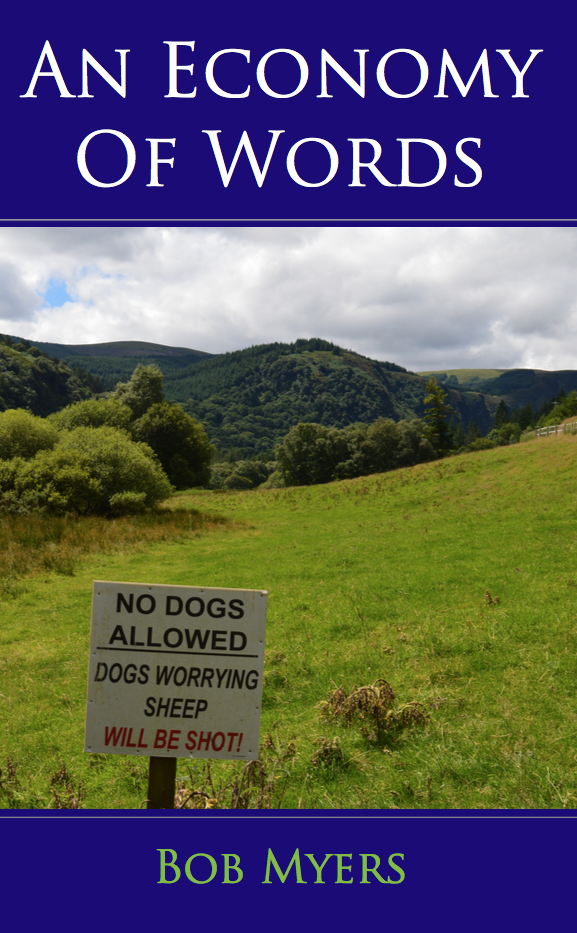

The following is my “Publisher’s Foreword”, which I wrote for my dad’s book of collected poems, “An Economy Of Words“. Now that Mom and Dad have seen it, I can share it with all of you. ~Bren.

If you are not one of the author’s nearest friends or family members, then this foreword is for you.

We would like to know how you found this book. We were planning a very small print run: perhaps only fifty copies, to be given as gifts to a handful of the author’s nearest and dearest. Did you find it at a charity sale, or in a box in someone’s basement? Was it holding up the short leg of a table? Or hidden under the cushions of an old chair, where someone accidentally dropped it? We’d like to know. For one thing, we’d like to track down that rotten sod who lost this book or gave it away, and demand from him an explanation. It had better be a good one. For this book is the author’s heart.

Bob Myers was born 1945 in county Laois, Ireland: a part of the country where, as he says, “the tourists never go”. His childhood consisted in getting lost in fairy rings on the way to school, hiding from the BanShee (that’s how he pronounced it) whose comb he had found on the road, and wondering what the kids in the Protestant school looked like. He came to Canada when he was eleven years old, studied English at the University of Guelph, got married, became a school principal, and bought a house in Elora to raise his seven children and they all turned out mostly fine. The rest of the details, you shall have to figure out for yourself by reading the poems.

He says they’re about ordinary events. Nevertheless, here’s over seventy years of them: some beautiful, some disturbing, and some deeply weird. Together they are his memoirs in verse, his autobiography in art, his voice crying out in the desert, his celebration of the ordinary life. And that is no ordinary thing.

Now, the observant reader will notice that in the first sentence of this book of poetry, a book which happens by non-coincidence to be full of poems, Myers denies being a poet. What a strange lack of grasp upon reality! In fact I wonder what other features of his world have not been approved by the Committee. For in this book you will find fairy stories, ghost stories, stories of childhood’s follies and elderhood’s nostalgia, love songs, travellers tales, fragments of conversations with the souls of others and the soul of the world, delivered with the irony and dry whimsey of Stuart McLean or Stephen Leacock. But it’s not the ghosts which are the problem. It’s his style of whimsey, isn’t it? You’d have to know the sound of his voice to get the whole effect. Without it, some of this stuff — the first few lines of Penance, for example — might sound a little creepy. As for most of the rest of it: well, in this modern age we are supposed to be self-absorbed and cynical! So, I am withholding one last poem from the collection. Our modern age doesn’t deserve it. It’s quite irrelevant that his last poem is a recipe for barbecued ribs with honey-mustard sauce. I’m keeping it for myself. Unless this book is in the running for a literary prize. Then I might share it with the judges.

You will also notice, because you are probably not blind, that many of these poems are also works of serious Christian devotion. Myers is the sort of Catholic whose Catholicism is sometimes too much for other Catholics. He is too fun-loving and intellectually curious for the puritans: for him, God is “in my flower garden / playing with my child.” A sentiment like that is worthy of Kalil Gibran. At the same time he is too conservative and ethically uncompromising for the reformers: this same god will dispense “direful justice” in the Endtimes. Since you’ve already read this far into the preface, you might as well know where all this religious intensity comes from. Of course he was religious from a young age. But in his midlife, his body became host to several incurable viruses with unpronounceable names. These microscopic monsters traded his bodily energy for a constant background of physical pain. His religious faith was his rock in the weary land. It allowed him to see how everything in the world has its place in the choir — including his suffering. These poems are his testament of a faith that allowed him to turn his frustration and anxiety into art. I dare say that his endurance of his physical disabilities (slogging along the Camino Sketches, for example), his perseverance through a traumatic childhood (see Contrition), his integrity in the face of social ostracism (see Kitchen Photos), the preservation of his generosity and his sense of wonder throughout, is the kind of quiet heroism for which other men have been beatified.

He wouldn’t want that, though. He would likely settle for seeing a copy of this book on a friend’s beside table, dog-eared, coffee stained, scribbled full of notes — evidence that it made someone happy for a while.

All right, then. Enough about the man. Enough of this prologue, too. Time to sum up.

If you’ve wondered what it would be like to visit a world full of ghosts and fairies and angels, where people spend long afternoons eating big home-cooked meals, drinking good wine, and arguing about the wherefores and the whytos of things, and where a nearby God presides over everything, well then here’s your book.

And if the style of these poems isn’t modern enough for your taste, that’s okay. This book wasn’t meant for you anyway. Drop it off at a charity shop. Maybe someone will pay two dollars for it, and maybe there’s a medical researcher who needs the money.

But first, consider the following. This book is my father’s heart. By way of some wandering path through time and space, it has landed in your hands. Maybe there’s something in it that was meant for you, after all.

Although I don’t really expect anyone will buy a copy, here’s the book on Amazon where you could do so if you were curious enough.