In the late 1980s, someone gave my dad a copy of Whitley Streiber’s Communion, a novel about an alien abduction. The front cover featured a head and shoulders portrait of a being which, today, is commonly called a ‘grey’: an alien with large and slanted almond-shaped eyes.

For no reason that I can fathom even to this day, the image utterly terrified me. I couldn’t look at it. I’d have an almost violent reaction: I had to cover my own eyes, or demand that someone take the book away. Dad kept it separate from the rest of the books in the library, and read it with the front cover folded back.

Today I have more self control: I can look at similar representations of aliens in The X Files, or Stargate SG1, without a sudden freakout. (Although it does still give me the creeps.) Nonetheless, I sometimes still wonder why I had that reaction. I am not, to my knowledge, an “abductee”. I’ve never seen a UFO for myself. I know that thousands of others say that they have seen one, including friends of mine who I regard as rational people and under situations where no alternative explanations were obvious. I would say that I would like to see one, but then I remember what it was like when a picture of a “grey” would cause me to have an irrational and physically visceral fear reaction.

Besides that: “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” If I was shown a UFO, I would demand a very high standard of proof that it wasn’t a hoax.

The famous scientist Stephen Hawking once wrote that if humanity encountered an alien civilization, it would likely go very badly for us. (Read about it here.) A simple version of his argument goes like this: first contact between high-tech and low-tech societies tends to go very badly for the low-tech society. As the contact between Europeans and Indigenous nations in Africa, Australia, the Americas, etc., went very badly for the Indigenous nations, so would the contact with (presumably very technologically advanced) aliens likely go very badly for us. “Because: empire, and colonialism”. I probably need not say much more about it than that.

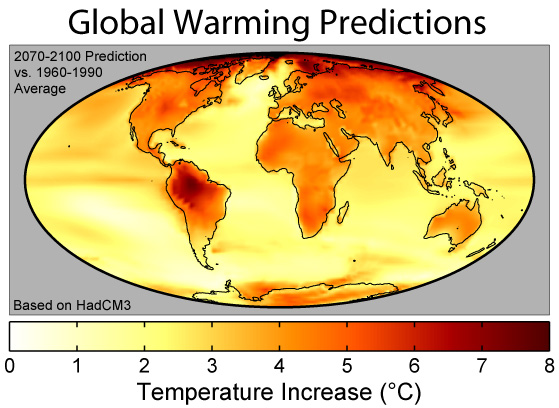

There are also arguments for why alien civilizations might be benevolent. A simple version of this argument goes like this. As a society develops its technology over time, it encounters “barriers” or “great filters” which might prevent them from progressing further, if not destroy them entirely. Runaway climate change, pandemic disease, weaponized AI, nuclear war— take your pick. Presumably, a civilization which has developed warp drive and contacted us will have overcome those obstacles. They might have learned how to run their economics, politics, ecology, science and technology, etc., non-hazardously and sustainably. And if they let us learn from them, it might be a net benefit to us to meet them.

Let’s see if it’s possible to split the difference. We could say, more simply, that a civilization-to-civilization encounter with extraterrestrial intelligent life would change basically everything. It would be comparable to the way human life on earth changed, and continues to change, because of the invention of the gasoline engine, or the spread of the internet, or the rise of our global climate instability crisis, as examples.

Okay, splitting the difference like that makes the proposition vague and evasive. So, here are some examples, that we can explore in a utilitarian way. Alien contact: how would it change how we think, and how we live?

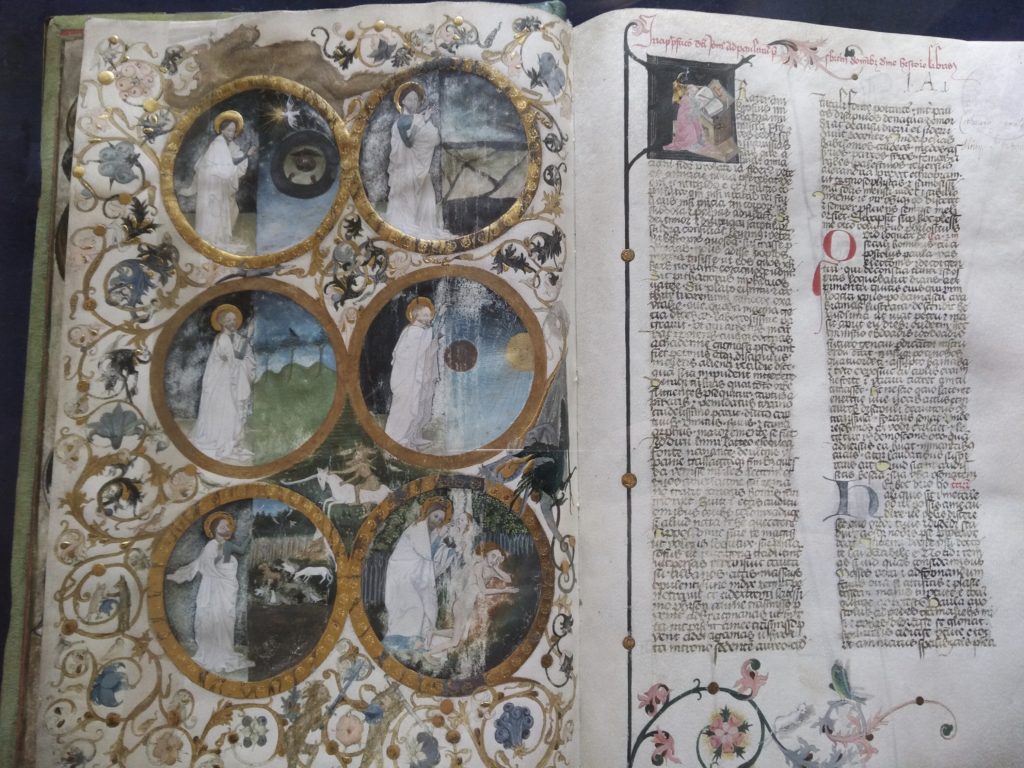

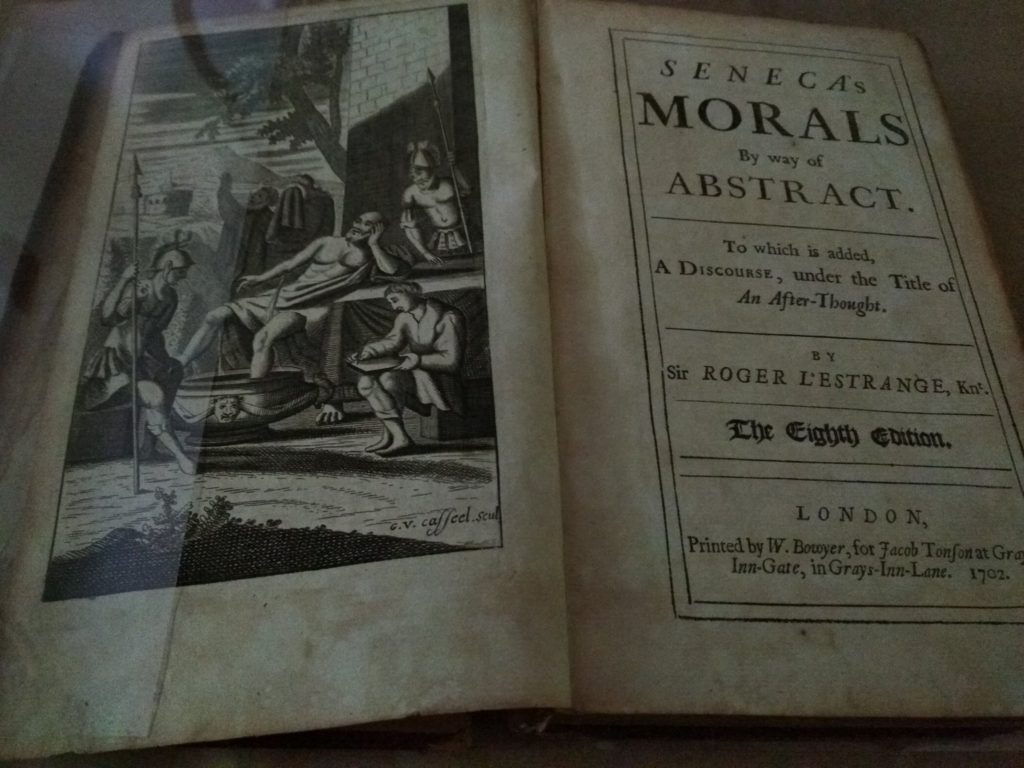

In religion: what if we were given unambiguous evidence that the Von Daniken Hypothesis is true? (In case you don’t know, that’s the theory, proposed by Eric Von Daniken in his book “Chariots of the Gods” (1968), that most of the world’s important global religions were founded by aliens who visited us in the distant past.) That would overturn thousands of years of human thought, feeling, art, music, architecture, social and cultural experience. There might be a massive shift toward atheism and secular humanism. At the same time, alien cargo cults might arise, in which people pray to the aliens for a solution to our global climate crisis, or to end all human wars, cure all diseases, or to bring some kind of personal salvation. Imagine what the world’s great religious monuments would look like— the Hagia Sophia, St. Peter’s in Rome, Kajuraho Temple, the Masjid al-Haram, and so on— if it were proven beyond reasonable doubt that the people who built them were wrong about their religious beliefs. Imagine what would happen to Christianity, the world’s largest religion by number of adherents, if Jesus came back to us and he had brownish skin, a wedge-shaped head, an extendable neck, no hair, and he waddled a bit like a duck when he walked?

In politics: As most everyone probably knows, political identity and unity often forms in a kind of dialectic relation between a constructed ‘us’ and a constructed ‘them’. Even the writers of Star Trek, a pop culture franchise which wears its humanism on its sleeve, proposed that the Federation was born out of a need for several different communities to unite and defeat a common enemy, the Zindi. Now, imagine the ultimate ‘us’, all human beings on Earth, configuring themselves in relation to an ultimate ‘them’— an intelligence so different from ours that it is literally otherworldly, literally not human. One could imagine the appearance of the political will to unite the 200 sovereign nations of Earth into a single body politic, so as to create interstellar economic and diplomatic ties. One could also imagine new strains of xenophobia and exceptionalism, and new strains of that pernicious political style which emerges from xenophobia and exceptionalism: fascism.

In art and culture: After ‘contact’, all stories will be science fiction stories. We would all be living in a bigger world, and no artist, writer, musician, filmmaker, game designer, or any other kind of creative person, could ignore that. Literary fiction, contemporary dramas, romantic comedies, and all kinds of other genres which normally have nothing to do with science fiction, would almost require some kind of alien contact point in order to keep up with the times. As a literary device, an alien is always a statement about ourselves: what we wish for, what we fear, how we approach differences among ourselves, what we imagine we could become, a warning about what we must never become, and so on. After contact, an alien could be just another character among many. Imagine a future version of Agatha Christie’s “Murder on the Orient Express”, in which the train is a spaceship, and a given character’s membership in an alien species is absolutely irrelevant to whether that character is one of the suspects. Or, the detective.

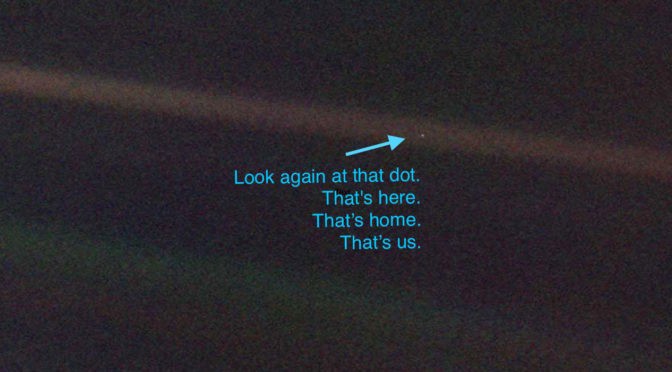

in philosophy (especially existentialism): after ‘contact’, it will be absolutely undeniable that there is nothing special about humanity. We will know ourselves as one species of sentient life among many, with no greater claim to significance than any other. Centuries ago, people believed that the Earth was the centre of the universe. Later we learned that the sun was the centre of our solar system. But we still thought ourselves special, ‘made in the image of God’, or otherwise possessors of a divinely-bestowed importance. After that, we learned that the universe is enormously bigger than our own solar system, and that it has no centre. But we still thought ourselves special: because of our ability to reason, for example. Or our uniqueness in an empty universe. After contact, the universe will not be as empty. And our rationality will be one kind among many. Our interests, our affairs, our lives, will feel smaller. It will be harder to ignore that we occupy only a tiny pale blue dot in an unimaginably vast cosmos, that is mostly as indifferent to us as we might be to a single spider on another continent. Thus the prospect that aliens exist can be equally as terrifying as the prospect that we are alone.

In some of those examples, it’s easier to imagine that alien contact would be bad for humanity, more than that it would be beneficial. And besides that, I have my own aforementioned personal reason to dread the prospect of meeting E.T.

Score for Hawking, perhaps.

But the damn thing of it is, I really do want to know if there are other intelligences out there. I think the core problem of the Fermi Paradox, the question “Where is everybody?”, is among the top-ten most important scientific and philosophical questions of all time. I am heartened by the fact that in the years since Frank Drake formed his famous equation, we have more information about some of its variables, so we have a better idea where to look for organized signals. I am deeply unhappy that I will very likely not live long enough to see the creation of a working Alcubierre Warp Drive— if such a thing can be built at all. Because I think that of all the things we could pursue and possess, the most important and intimate of them is knowledge. I want to see the rings of Saturn for myself: not only through a telescope— I’ve seen them that way already— but standing on the surface of Enceladus. I want to see the Great Spot of Jupiter, rising over the crest of a hill on Ganymede. I want to see a new star born in the heart of a stellar nebula. I want to see what our galaxy looks like from outside. I want to see an alien city, read their history books, visit their museums, explore their forests and tallgrass meadows. I want to know how they survived their wars and other great barriers, to the point where we could learn from them how to survive ours. I want to know what’s really going on in the universe. I want to invite the gods to my home for afternoon tea, to ask them Socratic questions, and find out what more and what else the meaning of life might be.

And I want to know if anyone else wants those things, too.