If you know anything about Greek mythology, you probably know some part of the story of Prometheus, the hero who stole fire from the sun and gave it to the fledgling human race. You probably also know how Zeus punished him for it, by chaining him to a mountain and sending a vulture every day to eat his perpetually-regenerating liver. The story still informs much of Western civilization’s sense of itself: his theft of fire is the symbol of Western civilization’s sense of its industriousness and enlightenment. Prometheus himself is a model of the ideal civilized man, a hero of daring and of endurance under adversity, combining the features of biblical Adam, the primordial thief, and Christ, the victor over death and the benefactor of humankind, and (though it may seem odd) Milton’s Lucifer, the rebel angel. We put the image of his torch in the logos of our corporations and our universities. We re-enact part of his story in the opening ceremonies of the modern Olympic Games, when we light the Olympic flame.

Ya, that was awesome, wasn’t it?

Nonetheless, I think Western civilization needs a better symbol.

For one reason: in the full story, Prometheus has no particular feelings for humanity. He delivered fire to us in order to undermine the authority of Zeus; he had no other reason. Indeed, humanity already had the technology of fire-building. Prometheus meddled with the sacrifices at a religious festival in Zeus’ honour. Zeus punished him by taking fire away from us. Only then, did Prometheus steal it back. And he didn’t carry it in a torch. He hid it in a stalk of the fennel plant. Various primary sources, notably the Library of Apollodorus, attest to this.

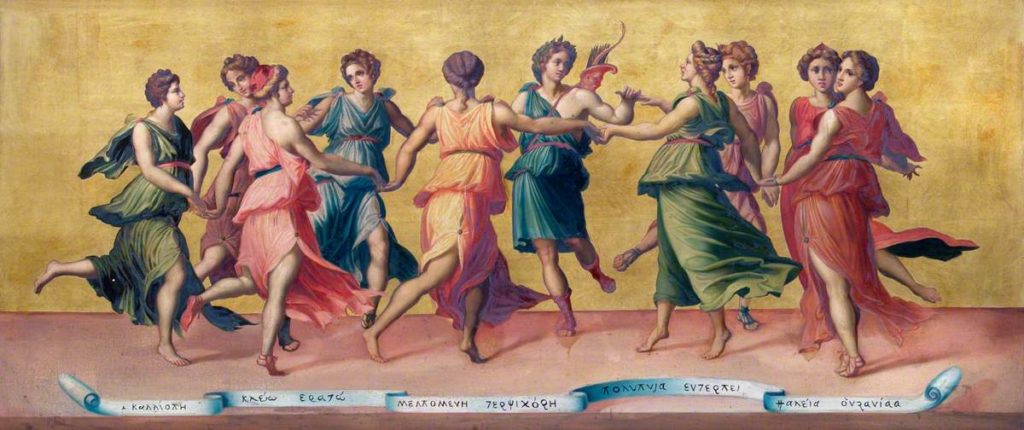

For a second reason: Greek mythology also provides to us an entire family of other, better benefactors: the nine Muses, who embody the functions of civilization rather more directly, if somewhat less ostentatiously, than Prometheus. The muses, and not Prometheus, are invoked at the beginning of the most important epic poems, the Illiad, the Odyssey, the Theogony, and the Works And Days. They’re invoked at the beginning of many of the old Greek plays, too. And while Prometheus and his torch are undeniably powerful symbols for industrial civilization, it is the gifts of the muses which activate the imagination, the artistic genius, and the scientific curiosity, which drives civilization forward. Indeed the very notion of ‘going forward’, or progress, is a gift of the mother of the muses, Mnemosyne, ‘memory’. For it is our ability to remember the past that enables us to possess a notion of progress at all; it is memory which allows us to compare our present state of life to the past, and so assess whether our lives are any better, or any worse, or at least different. And if we find that our life has become worse, we can call the muses to help us make art and so ease the misery, if not also improve life again.

For a third reason: when you look at who the nine muses are as individuals, you find they embody the foundational and essential fields of primary education: three poets, two playwrights, an historian, a singer, a dancer, and a scientist. That is to say, they teach intellectual knowledge, emotional maturity, artistic excellence; they are the bringers of the instruments by which we invent and discover our cultural identity.

Consider as an example, how culture might be different if, inspired by Terpsichore, primary schools had dance classes instead of or alongside gym classes. Students could learn a form of physical education and health maintenance which, unlike track-and-field events or field sports, is not a thinly disguised preparation for war fighting. They might learn how to move and use their bodies as instruments of fun and self-expression. They might learn how to touch and hold each other with respect. They would certainly build up muscle mass. (Ballerinas are really athletes, you know.) With that in mind, the symbol of the torch-wielding Prometheus seems to me unnecessarily aggressive, possibly vainglorious, and even rather joyless.

For a fourth reason: One can imagine any of the muses, even unhappy Melponene, singing or laughing with childlike delight to see some thing of beauty in the world, however small. One cannot imagine Prometheus laughing, unless it comes from a Nietzschean sense of pleasure in the exercise of power. And one cannot imagine him singing.

(Okay, fine, you can imagine him singing, and wearing a clown suit and juggling seven live cats, because imagination is weird like that. But it wouldn’t be consistent with his character.)

By contrast, the laughter of the Muses comes from pure life-affirmation, nothing more and and nothing less. Between the two, I think the laughter of the muses is preferable. It can come from that thrill you feel when life surprises you with something beautiful. That’s what inspiration is like, sometimes.

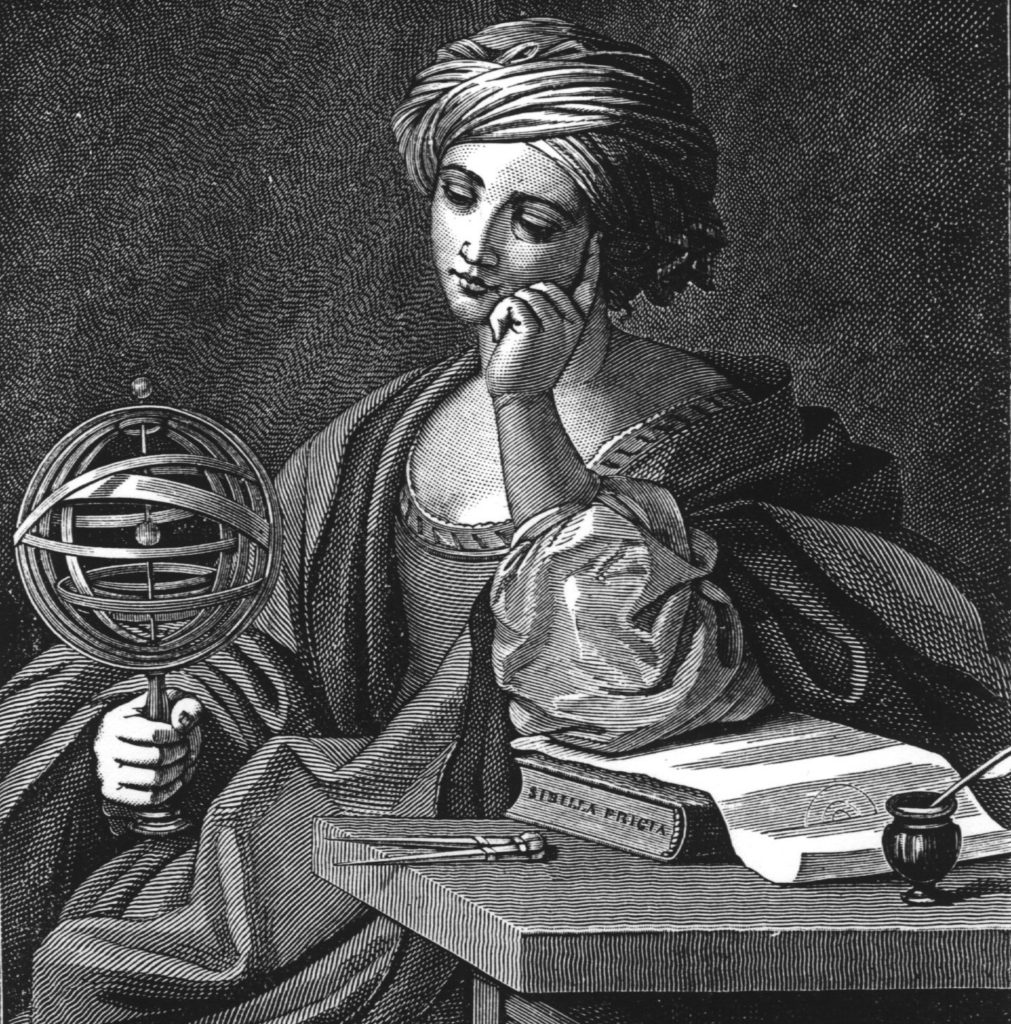

For a fifth reason: images of the muses already posses an important place in the history of western art. They were a special interest of the Italian Renaissance masters, for instance. Raphael included them in his Parnassus, his allegory of the arts, which occupies an equal place beside his Disputatio (theology) and School of Athens (philosophy).

Among the early modern depictions we find a dimension of the muses not well attested in the ancient sources, but nevertheless (so it seems to me) consistent: their sex appeal. The muses approach their students as lovers; their students try to court them with works of artistic aréte, excellence. And as most artists will tell you, the feeling of artistic inspiration and ‘flow’ is as good, and sometimes better, than sexual ecstasy. In this relationship of artist and muse, sexual identity, desire, and pleasure is affirmed as an ethical good. This seems to me a far better message than the one that tends to appear most often in pop culture, the message that men’s bodies are weapons of conquest and that women’s bodies are territories to be conquered. The sexual presence of a muse is not only a feature of their historic representations; sexual pleasure is one of the arts they teach: Erato, whose name needs no translation, is one of their poets. This affirmational view of sexuality might be especially important in places where the schools teach abstinence (by the way: the lessons don’t stick), or where the schools are removing mature sex education from the curriculum.

It might be argued that the renaissance depictions are fraught with what contemporary feminists call the male gaze: that is, the muses do not appear as persons with agency and independent identity, instead they appear as objects of possession and pleasure for a male viewer. This is a theme in western art in general (see episode 2 of Berger’s Ways of Seeing for a close study of this). If that is so, it seems to me the correct counter argument is not that we must cover or reject those images. Instead we should create new representations of our own, in which sexual identity, sexual pleasure, and sexual desire, can be affirmed in a manner that disempowers or dehumanizes no one, and in which the phenomenological relation between inspiration and sexual power can be affirmed, explored, experimented with, and enjoyed. I can imagine the muse-goddess Erato teaching a primary school class about consent culture, or the pros and cons of various contraceptives.

For a sixth reason: The dudebros reading this, who even now are hammering out angry skreeds against this argument, really have no reason to feel excluded. At least two men feature in the story of the Muses: Zeus was their father, and Apollo was their teacher, for instance. Feel free to use my comments section below to discuss whether the Muses could have grown beyond their teachers, as all good students do.

For all such reasons, then, I think a better symbol for the life and identity of western civilization should be a circle of the nine muses dancing together. It is a more joyful image, to encourage a more caring, more intellectually vigorous, and more artistically flourishing culture.

A counter argument. The identities of the muses, that is to say the selection of arts which they embody, is a kind of statement, to the effect that the selected arts constitute the goodnesses of life. This prompts the question: why those arts and not others? Why not painting, sculpture, architecture? Why not any ‘homely arts’ like knitting, cooking, weaving? Without them, the muses as a new symbol of civilization might be incomplete. Prometheus, by contrast, gave us a gift that everyone can use.

One reason for the selection of arts comes from the animism at the heart of religion. In ancient Greek paganism, material artists like sculptors and architects would have prayed to the spirits dwelling in the stone they worked. Artists would have prayed to the plants and minerals that provided their paint pigments. The nine muses represent arts that have no material foundation but the movement of human bodies and the thoughts within human minds (notwithstanding that they do carry props with them: books, musical instruments, etc., but these are icons of their bearers, and not materials that the worshippers work upon.)

But that is perhaps a religious-archeological explanation. A philosophical explanation might be that the muses represent activities instead of things; they inspire the pleasures that come from doing something instead of from making and owning something. (obviously, ‘making’ is a kind of ‘doing’; but let’s not quibble). The work of the muses can be accomplished and completed in its moment of creation, and the work vanishes as the moment passes; the work of a sculpture or an architect reaches completion only when the artist ceases the activity of creation. Then the work of that activity remains, as an object that can be priced, bought, and sold. All that is to say, the muses inspire activities that have a different relationship to time, and that different relationship to time allows them to escape capture by the market. Poetry is meant to be read out loud; music is meant to be sung; history is for telling; the stars are for observing. It could be further objected that a dancer could be paid for her performance; a historian or a poet could sell copies of the books she wrote; an astrologer could collect a fee for her professional consultation. But no one can own a moment of beauty. No one can own the stories of the past, no one can own the stars. We can only see, hear, and remember such phenomena; it is therefore all the more fitting that remembering is the mother of the muses.

Well, that reply to the counter argument is not fully persuasive. For in much the same way, you could own a statue but not its sensuousness; you could own a painting but not its light, you could own a building but not the frozen music it embodies.

Perhaps the simpler answer is to suppose that since thousands of years have gone since the mythic age, the nine canonical muses might have diversified their portfolios. Maybe Thalia, muse-goddess of comic drama, now inspires the authors of newspaper comic strips. Perhaps Euterpe, the muse-goddess of lyric poetry, also inspires the people who design light shows at rock concerts. Perhaps Polyhymnia conducts gospel choirs.

It’s easy to imagine those new possibilities because the Muses, as symbols, are adaptable to new circumstances. And in that way, they can meet the counterargument noted above: that their symbol might be incomplete. I rather think that the muses can always fit themselves into new arts, new forms of expression. They can be by your side at any time.

Prometheus, as a symbol, seems to me somewhat less flexible. He’s a straight-up hero, a trickster-god, a rebel angel; and while those are good things to be, he’s not much else. I think it’s Prometheus, as a symbol, who is incomplete; its hero-energy might be remain reactionary and aimless, without the vision and guidance of the muses.

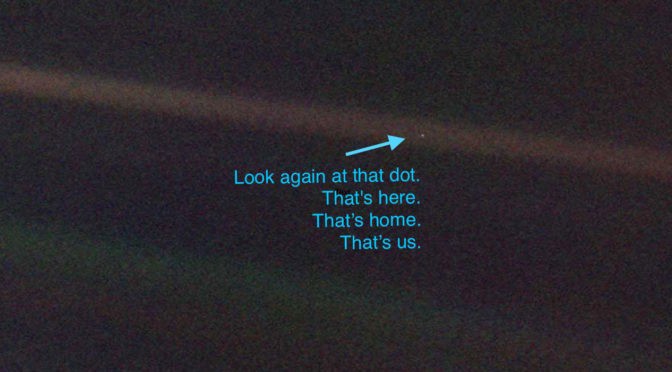

I have it on good authority, by the way, that Urania, muse of astronomers, is now a flatmate with Saint Sophia, the goddess of philosophers. She was in the JPL control room when NASA launched the Voyager probes. She once had a beer with Carl Sagan and Stephen Hawking.

In fact, I’m writing a novel about that beer.

In fact, I’m having a beer with her right now.

So, if you don’t mind, I have to get back to work.

Postscript 1: For the sake of reference, here’s who they are, and how to translate their names.

Calliope, “Beautiful Voice”, epic poetry.

Clio, “Make-Famous”, history.

Euterpe, “Giving Delight”, music, song, and lyric poetry

Erato, “Beloved”, love poetry

Melpomene, “Celebrates With Song”, tragic drama.

Polyhymnia, “Many Hymns”, religious song

Terpsichore, “Delighting In Dance”, dance

Thalia, “Rich Festivity”, comic drama.

Urania, “Heavenly One”, astronomers.

Postscript 2: The (draft) cover copy for the novel that I mentioned above.

On a cold night in 1514, Urania, the Greek goddess of astronomy, inspires Nicolaus Copernicus to re-imagine the cosmos with the sun at the centre: a crime for which Zeus banishes her from Olympus. Then Julian Augusta, former emperor of Rome and an agent of Zeus, offers her a bargain: find one mortal who can grasp the immensity of the universe without going mad, or else live in exile forever. With help from Prometheus the Titan, and Kynisca of Sparta, the first woman to win at the Olympic Games, Urania works with Tycho, Kepler, Galileo, and other great names of the Renaissance, hoping that one of them can win the gamble. But Julian arranges for accidents, turns of fate, even the Inquisition, to interfere with their work, and Prometheus has his own agenda. As her search continues, she finds the consequences of winning might be worse than the price of losing.