On 1st November 1755, a Sunday that year, a powerful earthquake struck Lisbon, Portugal. The quake itself and the wildfires and the tidal wave caused by it destroyed most of the city, and killed an estimated 60,000 people.

Lots of people back then said that the earthquake was sent by God to punish them for their sins, Old Testament style.

I’ve noticed some similar comments from people on my social media, and in the news, in reference to the three hurricanes that have struck or are about to strike the USA, Mexico, and the Caribbean. Some from Christians who say the hurricanes are sent to punish the sinful persons of their choice: abortionists, trans people, gay people, liberals, whatever. I have also seen a few greens and environmentalists pronounce the hurricanes a just punishment for America’s love of the oil & gas industry, and its pursuit of industrial capitalism in general.

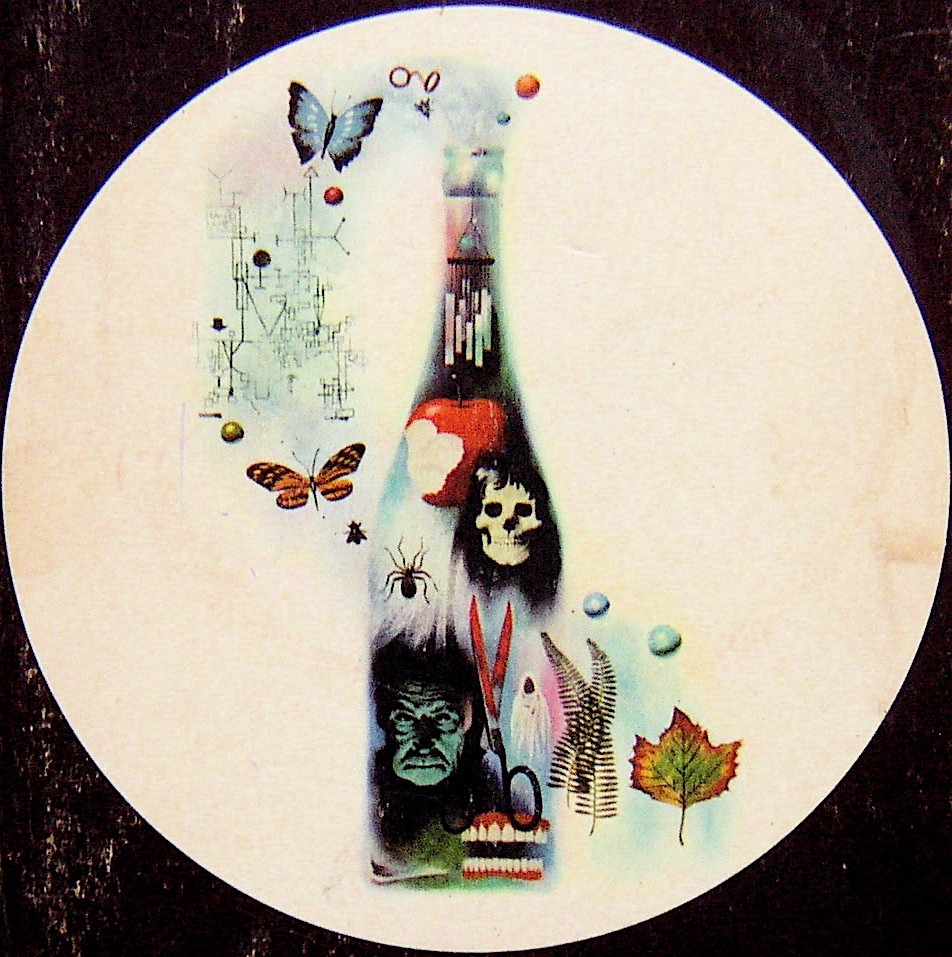

Infrared satellite picture of hurricanes Irma, Jose, and Katia, as seen on 7th September 2017.

The earthquake in 1755 produced big changes in European culture. Seeing that lots of perfectly moral, God-fearing, probably mostly innocent Christians died in that earthquake, people began to think it likely that natural disasters had nothing to do with their sins. People didn’t become atheists overnight, obviously; philosophers like Voltaire and Kant, who wrote extensively on how nonsensical it was to connect the quake to God’s wrath, nonetheless remained religious men. But it did change the way people thought about their relationship with God, and it changed the meaning of their faith.

I wonder how religious culture in America, and the world, might change as a result of these three hurricanes.

There is at least one way in which the hurricanes of 2017 are different from the earthquake of 1755. The hurricanes were predicted in advance by scientists. Not that they predicted these exact three storms on these exact dates. But they did predict that global warming and climate change would lead to more storms and bigger storms. There are a few associates of mine right now whose Twitter and Facebook feeds have become a steady stream of “I told you so!”

(Which isn’t helpful. In fact it’s likely to alienate the very people who need to be persuaded to appreciate science better. But I digress.)

The fact that these storms were predicted, in broad strokes if not in fine detail, makes me wonder if more people will turn away from the Bible-thumping, foaming-at-the-mouth moral-panic-instigators who have insisted that climate change isn’t happening, or that it is happening but we deserve it, or that it is happening but we don’t need to do anything about it because when human suffering reaches a pinnacle of misery then God will come down from heaven and save us. Yes, there are such people, and they have bully-pulpits that reach millions. I’m sure those people won’t go away. But as “God’s judgment” continues to look more and more random in the people it kills, might the preachers of God’s judgment look more and more wrong?

I suspect that religious people are about to have a big discussion of a new form of the old ‘problem of evil’. If we believe, as most religious people do, that the gods care about humanity, why do they not prevent natural disasters? How can we see the divine in the hurricane that destroyed your city and killed some of your loved ones? And indeed, what shall we make of the apparent fact that the storm selected the people it killed at random?

Is it because the gods have some reason not to interfere in the world, as in the old version of the problem?

Or— here’s the new part of the old problem— if the gods reveal themselves in the world of nature (by the way, there’s a perfectly sensible way for monotheists to understand this proposition; you don’t have to be pagan to believe it), then what are we to make of the fact that some of those natural revelations are disasters and that science can predict them in advance?

Is it because the gods are not powerful enough to prevent those storms? In which case, is there still much point in worshipping them?

Or, is it because the gods are those storms? (Now that would be a pagan point of view.) In which case, how could you relate to them? I suppose you could make expressions of awe, and then offer propitiatory prayers (“Dear god, wow you are so big, now please don’t kill us…”). But it’s hard to see how you could build a positive life-affirming worldview around that.

Or, perhaps “the divine” is not a person, but rather some kind of presence or force or ‘way’ of things, rather like the Tao, or the old Neoplatonic idea of the One-And-All. In which case, ‘worship’ was never the point, but we still need to ask what to make of the way science can predict its movements.

I’m sure lots of people will resolve these problems for themselves by becoming atheists. Remember your Wittgenstein: “the solution to the problem lies in the disappearance of the problem.”

But for those people for whom atheism isn’t an option, perhaps because they have known the oceanic feeling of immensity and one-ness which lies at the heart of personal spirituality, I think this conversation about the problem of evil will produce a new understanding of divinity. It will look nothing like the religions of the past and the present. It will call itself Christianity, or Buddhism, or Neo-Paganism, or whatever, but it will be a very different animal.

I make only this one prediction about it: whatever it will be, it will be less otherworldly and more human. By which I mean: it will acknowledge our human ability to make stupid decisions, such as those which result in the destabilizing of our climate, costing us millions of lives. But it will also acknowledge our human ability to solve our problems, work together, find solidarity with others no matter how different or disagreeable they are, and to dispel the illusions that hold us back from realizing our original goodness.

I predict this, because I think these beliefs follow from the realization that God will not save us from global warming, nor from war, injustice, oppression, nor any of our other problems. We will have to save ourselves.

—-

Addendum, a few hours later.

A friend of mine who read this blog told me she knew someone who saw these storms as a sign of the end of the world. So, in the future, religion might grow even more fundamentalist.

Well, I suppose that’s possible. Indeed, I think some people may want the condition of the world to grow worse, so as to accelerate the arrival of the Messiah. (Actually, I think that is exactly what motivates certain climate change deniers and authoritarian politicians.)

But I predict– no, I hope, I summon my confidence– that as the end of the world continues not to happen, more people will see that kind of apocalyptica for the silliness that it is.

Whether or not God exists, the future is going to be all about us.